Sitting Still

With a handful of books.

Hello from a remote village in South India. I have been here for two months and haven’t been writing because I haven’t felt like writing. So today when I did, after many weeks, I latched onto the feeling before it slipped away. But what do I write about? I haven’t been travelling or exploring new places. I have just been sitting still.

The dictionary definition of stillness is the absence of movement or sound. In spirituality, it refers to the mind being quiet, with a heightened sense of awareness, and at peace with itself and the world. Thoughts come and go, and we observe them for what they are, without reacting to them or being imprisoned by them.

I wish I was sitting still in this sense, but it’s been more of the former.

We often travel to remote areas to escape the chaos of big city life. The sound of horns, the polluted air, the hustle culture. Surroundings certainly have an impact on our mental and emotional health. But it only helps to a certain extent. It’s the mind that we have to train to be less busy, less attached to specific outcomes, and more at peace with whatever life brings our way. If you have read my post on Vipassana meditation, you would know that this is my go-to practice of attempting to calm the mind. To weed out past traumas, insecurities, cravings, and aversions. But I haven’t been doing much of this either.

Instead, I’ve been staring at the trees – trees of all shapes, shades, and sizes that grow around me. Kaju, jackfruit, mango, banana, chiku, pepper. I’ve been catching glimpses of the early morning sun rays and late evening sunsets through the leaves. I’ve been watching chickens run around and langoors jump from tree to tree while I take my work calls. I’ve been trying to meditate through everyday actions - the way the Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh encourages - when I’m drinking tea, making a meal, folding clothes, dusting my books, taking a bath, and watering the plants. Work has been hectic, as has life, and I feel tired. Too tired to think. Too tired to write. Too tired to do more.

In a world that celebrates hustle culture, hyper-productivity, and being occupied all the time, I am trying to rest. I am telling myself it’s ok not to write, not to make my weekends productive, and take my time to re-energise. Sometimes our minds, like our bodies, need rest – dedicated time to do nothing. Sleep, slow down, sit still.

Today I'll sit still.

When my dog shuffles over and offers me

his fleas and his soul, I'll turn away.

To everything I'll close my eyes,

slice the darkness and eat it.

I'll refuse to give money on a platter

or a wet kiss under the moon.

Today I'll just sit

and say No to everyone and everything.

To the book on my desk, it's sad tale

of abandonment, remorse and death;

I'll keep it on the tip of my tongue

like a lukewarm dime.

No to the daily mail with its greasy fingers,

no to the telephone and its humming

through the carcass of a sparrow,

no to every projection of the self.

No to me, this preposterous accident

who speaks of the "self."

Today I'll be anti-social.

Today I'll grow into myself, be the river

of my blood, the sky inside my eyes,

the maze of my ribs, the dust that settles

on my heart. I'll let my bones sink

like pebbles in a pond.

I'll let my feet grow roots and be an extra zero

on the checks that I'll refuse to write.

- Ernesto Trejo

So that’s what I’ve been doing. I don’t want to write for writing's sake, just as I hate to speak when I have nothing in particular to say. Writing aids thinking, and journalling almost always helps feel better, but writing for a larger audience ought not to be for the sake of it, and certainly not without contemplation. I have several themes brewing in my mind that I may or may not write about some day, but they’re in very nascent stages and need more marination. So today, I thought I would write about the books I have been reading and thinking about these past few months. They are all intense reads in their own way, but through them, I travelled to different worlds (Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Lahaul, Trinidad), lived many lives, and understood my own better.

1. The Naked Don’t Fear the Water

When does a migrant become a refugee? ‘The Naked Don’t Fear the Water’ is an incredible real-life account of a Canadian journalist and his Afghan friend taking the smuggler’s road to Europe. Equally a commentary on the consequences of war, globalisation, and a world driven by nationalism and capitalism. Matthieu Aikin’s chronicle of their journey is honest, chilling, gripping, humbling, and heartrending. A must-read for anyone trying to understand the times we live in, and especially the global refugee crises. The writing gets better by the page, although it felt a bit drab in the beginning, having started this book after reading a bunch of new-age experimental novels. However, the theme and content is riveting, making it hard to not get sucked in and appreciate the lengths to which the author went to document this incredibly risky journey.

2. Brotherless Night

Heartbreaking, deeply compassionate, and achingly nuanced novel about the human cost of war, ‘Brotherless Night’ is a must read. It is a fictionalised account of Sri Lanka in the 1980s — stories of countless families torn by violence, politics, and ethnic conflict. At the centre of it is a tender tale about 16-year-old Sashi who dreams of studying medicine and becoming a doctor - only to have the civil war change her life forever. The book is equally about the journey of civilians taking up arms to resist years of injustice and violence, radical movements spiralling out of control with their inherent hypocrisies, the politics of state power and “protection”, women finding new modes of resistance even as they are used as pawns by all, the cost of speaking up, and so much more. I wish this was pure fiction, but it is not. The novel draws from over two decades of meticulous research and documentation of Tamil people’s histories. It affected me a lot more having travelled through the Northern Province of Sri Lanka where I heard first-hand accounts of much of what is described in the book. I could see the scenes play out in front of me as I read page after page. Fiction helps us grasp history in a way that non-fiction seldom can. It hits you to the bone. The characters become a part of you and stay with you forever. V.V. Ganeshananthan’s brilliant storytelling, with its gentle yet unapologetic rawness, does full justice to what the book set out to do.

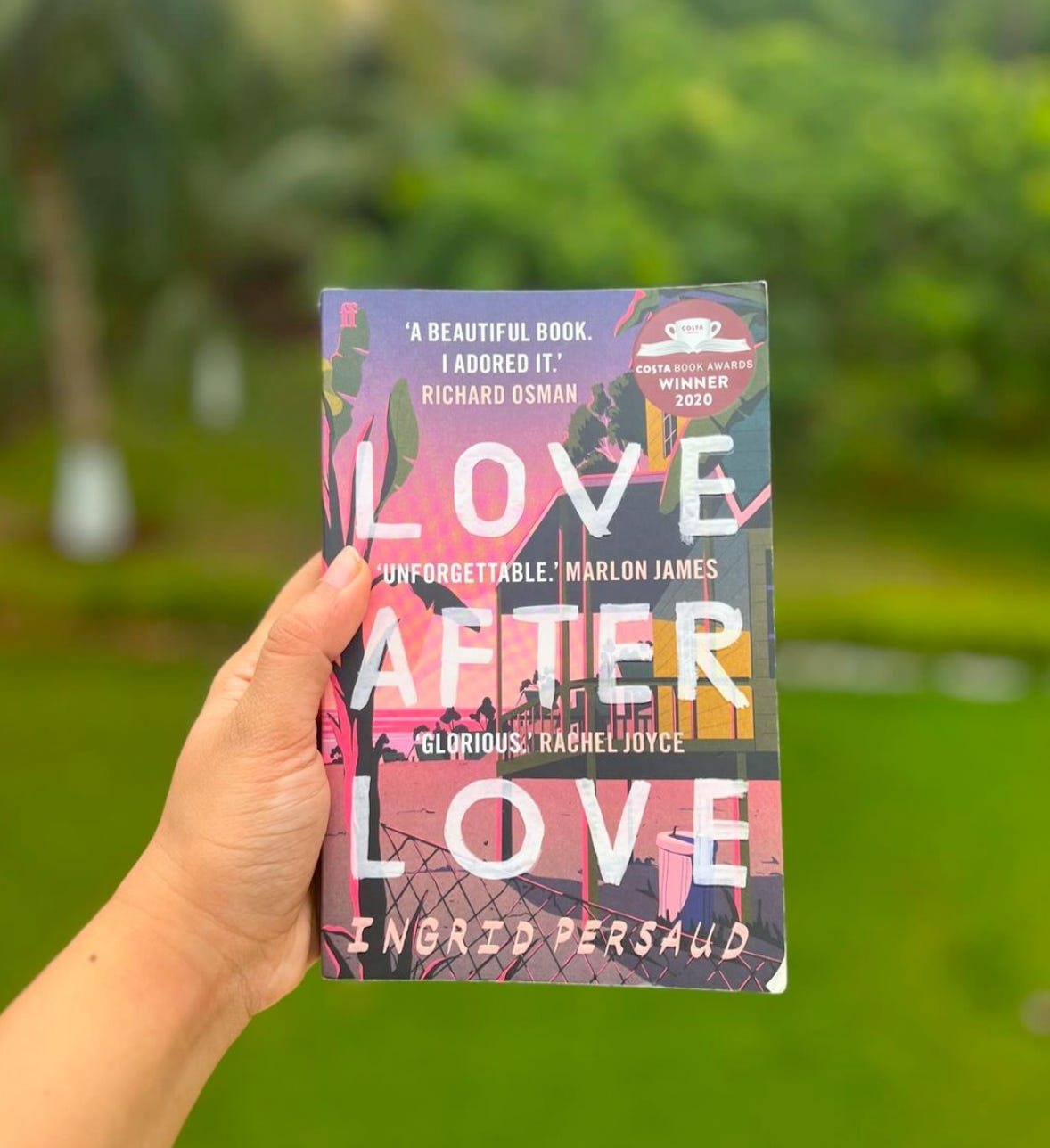

3. Love After Love

‘Love After Love’ is a captivating novel about love in all its forms - familial, romantic, platonic, self. Written by a Trinidadian writer in Trini-English, I could literally ‘hear’ the narration. It took a while to get used to the accent (represented by the spellings) but this added an additional dimension to the reading experience - something so hard to achieve through the written word. I have never interacted with a person from Trinidad, so this book reiterated the need to read more books from places we know little about and written by authors who push the scope of what a novel can be and do. It is by no means an easy read, but it will likely have you hooked.

Random trivia: I recently learned that 37% of Trinidad and Tobago’s population are of pure Indian descent!

4. Reflections on a Mountain Lake

‘Reflections on a Mountain Lake’ is a collection of Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo’s Dharma teachings and lectures. It is an incredible book for anyone interested in Buddhism, and especially women, who don’t have the same avenues as men even here. The topics range from her journey and experience as a woman walking the Buddhist path to the nuances of Tibetan Buddhism. It also gives conceptual clarity on the difference between Shamatha and Vipassana, the Vajrayana school of thought, awareness vs concentration, and so on. But what I loved the most is the feminist underpinning throughout the book - refreshing to read in a Buddhist world dominated by male monks and writers. Jetsunma also has a fascinating backstory herself - she lived and meditated in a cave in complete seclusion for twelve years - and later founded a beautiful nunnery in Palampur. She trained in a monastery full of men where she was the only woman, and despite all the barriers, discrimination, and roadblocks she faced, managed to carve her way through. I have had this book on my shelf for a few years now but visiting her nunnery and catching a glimpse of her recently propelled me to finally pick it up and read it. While a prior understanding of Buddhist principles is not necessary to read the book, I think it helps to have some background.

5. The New Saints: From Broken Hearts to Spiritual Warriors

‘The New Saints: From Broken Hearts to Spiritual Warriors’ is written by a Queer, Black, American, Buddhist Lama. It is a meditation on the intersections and interconnected nature of spirituality and activism in today’s world, the politics of violence and care, and the potential for each and every one of us to be human ‘saints.’ As someone who has worked in the social sector for most of my professional life, I was attracted to Vipassana and Buddhism because of people I met at work. So recognising the close connection between my spiritual journey and professional work is not new. However, books on Buddhism seldom speak to people working in the realm of social change (beyond concepts of compassion and charity) while books on social change seldom touch upon spirituality or how care ought to be at the centre of everything we do. This book is an outlier in this regard and touches upon themes that are seldom discussed together or in relation to each other. I am not sure how much of the ‘theory’ described in the book would make sense to someone unfamiliar with practices like Vipassana, but for me, reading it with some prior knowledge and practice of the concepts, was a delight. It helped me make sense of my own emotions and spiritual journey, and gave me a framework to make sense of how my personal and professional experiences converge.

One of the sections in the book that stood out for me was about the perception of goodness in society, and how it is dependent on the extent to which we conform to society’s standards and expectations. We are deemed a ‘good’ person/daughter/citizen/woman as long as we follow the status quo and don’t question patriarchy/authority/customs/rules of engagement. But as soon as we do, and don’t fit into the given template, we are shamed by society as being selfish, anti-national, rogue. For accepting our non-compliance would mean that those shaming us would need to confront their own life choices and insecurities, and the discomfort and existential crisis that might bring forth is scary. So the easier option is to shame us.

If you have read any of these books, or will after this post, I would love to hear your thoughts on them. I will sign-off with one of my favourite poems by Wendell Berry:

THE PEACE OF WILD THINGS

When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children's lives may be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

— Wendell Berry

Your posts are a balm for the soul. Picking up Lama Rod Owen’s book first. Much love, Ila!

It's been so long. I have a lot of catching up to do, but let me tell you that I felt uncomfortable after reading the opening few paragraphs. I hope you are in a better place now than when you wrote those lines.

One doesn't have to be productive all the time (of course, I take this to extremes by not being productive any time, but I digress), so please do not worry about that. Even when you are trying to switch it off, look at how intentional you are in ensuring no two pictures of books are clicked in the same background. That is you. I hope you are better now.