Whereabouts

Jhumpa Lahiri’s latest book and some hidden wonders of Delhi.

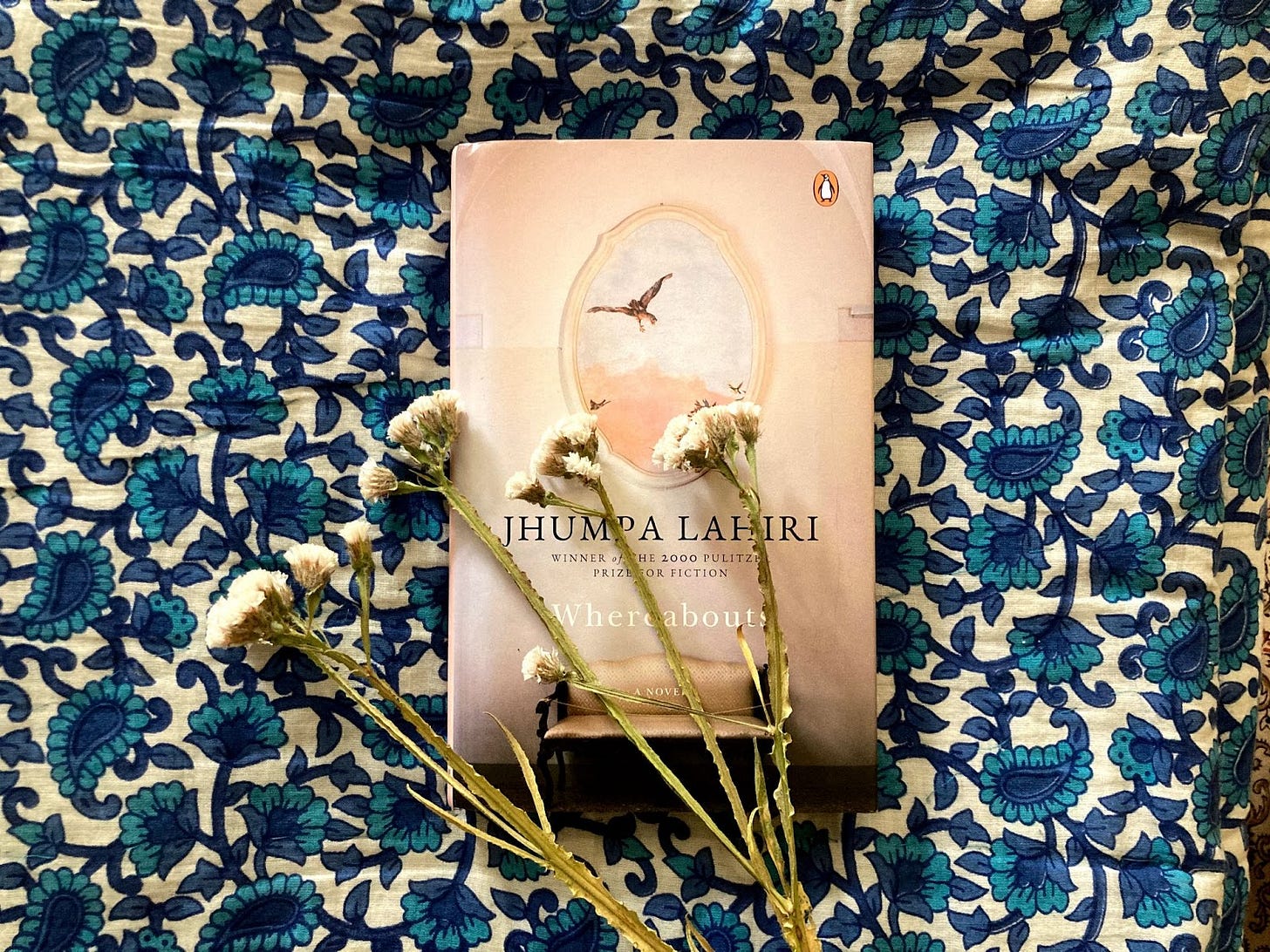

Last week, I picked up Jhumpa Lahiri’s Whereabouts with the hope that it would help me redeem my reading routine. It arrived in the mail over the weekend, and I’m happy to share that I completed it in two short sittings (an achievement in itself, as I have been struggling to finish books).

Originally written in Italian, Whereabouts has been translated into English by Jhumpa herself and is unlike any of her other books in style and treatment. The short chapters (sometimes just a page long), lucid writing, and simple plot make it an easy read, a blessing for current times.

Each chapter is set in (and named after) a place in an unnamed city in Italy: at a cafe, at the salon, on the bridge, or at the beach. Sometimes, we get a peek into the narrator’s mind — a 40-something single woman, coming to terms with her father’s sudden demise, her strained relationship with her mother, her fleeting relationships with lovers, and her own solitude.

The book celebrates the extraordinary nature of ordinary situations, places, and people — the ‘ordinary’ life from pre-pandemic times that we so miss. Through each chapter and setting, we get to know the narrator a little more: her personality, her thoughts, her relationships. The book explores the themes of connection and alienation through the narrator’s journey, and the many manifestations of solitude, sometimes bordering on loneliness.

Whereabouts is neither a happy read nor an uplifting book — but it is oddly comforting. It reminds me of my own relationship with my city, sometimes more intimate and long-lasting than my relationships with people. Every other neighborhood is attached to memories, fleeting encounters, and quiet observations from over the years. It makes me reflect on my own ideas of solitude and the feeling of disconnection from the people around me.

To summarize: I really enjoyed the book. It is somber but beautiful, simple in its complexity. And very, very relatable.

Here’s a lovely, detailed review of the book by Jennifer Wilson: A Solitary Trade.

Although I’ve lived in Delhi all my life, I started exploring it only in my early twenties. Going to college in North Campus, located at the other end of the city, meant commuting for over four hours daily by bus, metro, rickshaw, and foot. On many days, I would reach college only to find out (very often) that classes were canceled due to a strike, and a two-hour commute back home wasn’t appealing. So my classmates and I started exploring different parts of Delhi that were connected by metro or close to campus. These excursions were usually in search of cheap, tasty food, but in the process, I discovered unfamiliar parts of the city that expanded the map of Delhi in my mind.

This habit of loitering around the city stuck through time. When I started working, I meandered through new neighborhoods after meetings, walking from one metro station to the other instead of taking the train. I observed the architecture of each passing building, grabbed a bite from different street vendors, and got familiar with the area. This soon became my favorite way to unwind, overcome a bad mood, or simply get to know my city.

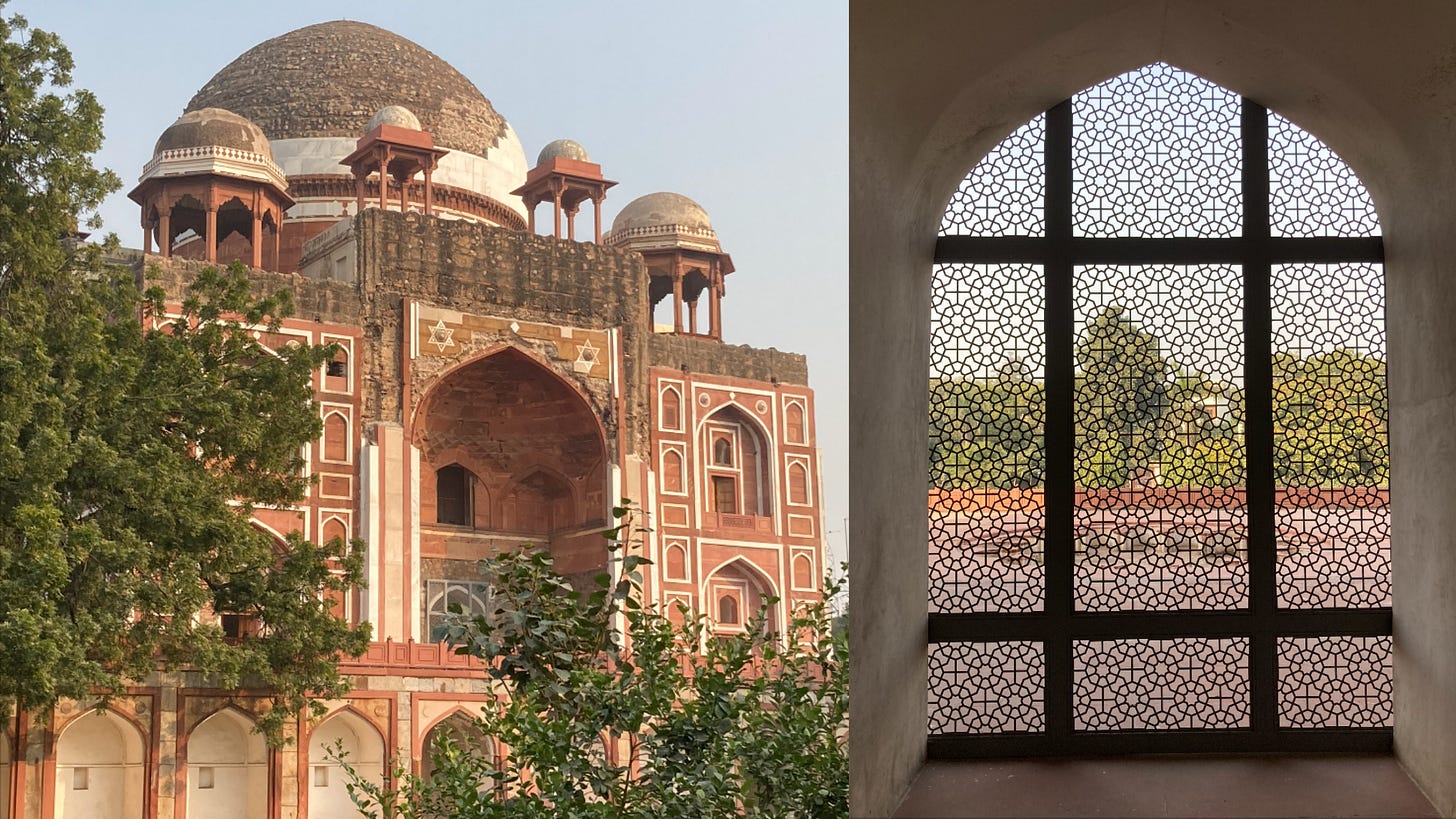

When COVID cases were temporarily under control last year, I started stepping out in the wee hours of the morning to visit some of my favorite places. Initially, I frequented Sunder Nursery and Humayun’s Tomb. It felt surreal to be amidst so many trees, flowers, peacocks, parakeets, and kites after six months of being indoors. Most of the time I was the only visitor as I went at odd hours. These places became my escape for a few weeks, but the crowds eventually caught up.

With Delhi-ites craving the outdoors post-lockdown, even people who seldom visited public parks flocked Sunder Nursery. It was good to see the place getting the attention it deserved, but it was getting more and more crowded by the day and I knew I had to find an alternate place for my weekend escapades.

One afternoon last winter, I set out to find Mohammad Wali Masjid. I knew it was near Sirifort Sports Complex (I had read about it online) but had never visited it. After ten minutes of walking around the area, I spotted a gate that had a lock but was slightly ajar, just enough to enter. I slid into what seemed like a small, well-maintained park. On walking further, I saw a row of trees and some caretakers sitting on the grass, enjoying their lunch. Such a lovely picnic spot, I thought; I had to bring my friends here!

I kept walking until the Masjid was on my left. I entered the complex, mesmerized by the patterned shadows cast by the carved iron gates and the sharp rays of the winter sun.

Made of a mix of quartzite and sandstone, the Mohammad Wali Masjid has three domes and is surrounded by a walled garden. The place dates back to the Lodhi period of the 16th century, and few people know about it, even now.

The inner walls are adorned with beautiful incised plasterwork featuring symmetrical patterns, medallions, and Persian calligraphy. While one end of the place opens up into a courtyard, a tiny opening with a steep, narrow staircase leads to the roof. The view from the top consists of treetops and nests, the group of caretakers mere dots at a distance. A fine discovery on a fine winter morning!

On another such outing a few weeks later, I visited the tombs of Mahbano and Abdul Rahim Khan-i-Khanan. Newly restored and re-opened to the public after five years of restoration work, the mausoleum was built by Abdul Rahim Khan-i-Khanan for his wife Mahbano in 1598. He was later buried at the same site in 1627. Along with Humayun’s tomb, it is believed to be the inspiration behind the Taj Mahal.

For the uninitiated, Rahim is known for his dohas (couplets) and Persian translation of the Ramayana, among other things. He was a Navratna, an important minister in Akbar’s court, and continued to serve in Jahangir’s court upon his accession.

Rahim and Mahbano’s mausoleum is made of sandstone. The inner walls, here too, have intricate incise plasterwork, jaalis, and domes, characteristic of Mughal architecture.

The tombs are located in the inner chambers and are closed to the public. The mausoleum is surrounded by a garden on all sides, which originally extended all the way to the Humayun’s tomb complex!

My last few outings before going into self-imposed lockdown due to the rising cases in my neighborhood (and city) were to nearby parks. By now it was spring and the flowers were in full bloom: magenta, orange, white, mustard…. every shade of bougainvillea imaginable. I started visiting a different park every week and it felt like I was re-discovering my city.

I’ve lived in various cities and small towns since college, but even when in Delhi, I’ve been so caught up with work and travel that my visits to these neighborhood parks became infrequent. What I love the most is that each park looks different in every season and over time, and is worth returning to time and again. Coming out of lockdown ensured that I treasured each park visit and experienced it with utmost gratitude and mindfulness.

For the first time, in autumn last year, I noticed countless resham rui (floss silk) trees around South Delhi. In spring this year, palash (flame of the forest) flowers were strewn along every path in my colony. Friends who saw photos from my walks couldn’t believe they were from Delhi. Friends who live in the same neighborhood asked ‘Where is this beautiful place??’

If there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s to never underestimate one’s own neighborhood. Aimless meanderings are precious, and sometimes we discover (or re-discover) beautiful aspects of places only when we experience them mindfully, like a traveler, rather than as a resident.

It feels strange to write about Delhi’s beautiful parks at a time when images of the Central Vista redevelopment project are circulating online. Heritage jamun (Malabar plum) trees in the most beautiful parts of Delhi are being felled. History, architecture, and memories are being erased overnight. While the city mourns the loss of lives and continues to scramble for oxygen and space in graveyards, we also mourn the loss of familiar, loved places — this too, from a distance.

Who knows what will remain of this city by the end of this pandemic? Who knows what will remain of us?

There’s a Persian prophecy mentioned in William Dalrymple’s City of Djinns that says that whoever builds a new city in Delhi will lose it. This has happened with the Pandavas, Prithviraj Chauhan, Ferozshah Tughlaq, Shah Jahan… even the British. They all built new cities and they all lost them.

One can only hope that things will end well for this beloved city. For now, Delhi in full bloom is my last memory of it outside the four walls of my house. This is how I’d like to remember it for as long as I can.

Loved the review. Makes me want to read the book. The passage on the trips were vivid and the photos were lovely.

loved the photographs and your easy style made me feel like I was sauntering along those 'lovely neighbourhoods that should never be underestimated!