From Empire to Astronomy: The Many Wonders of Samarkand

A Historical Exploration of Uzbekistan – Part II.

Read Part I of this series here.

“The story of Uzbekistan is the story of Timur,” said Rameen, on our first day in Samarkand. Timur brought large parts of Asia under an empire centered in what is now Uzbekistan, and Samarkand is the epicenter of his creations.

As one of the oldest inhabited cities in Central Asia, Samarkand has seen the rise and fall of empires, the flow of cultures, and the fusion of civilizations. It was an important city during the Sogdians’ rule, but became even more prominent as a trading post on the ancient Silk Road. It reached the height of its glory under Timur in the 14th century and his architectural legacy is still visible today.

Timur’s empire also became a beacon of learning and cultural exchange. Scholars and poets from different parts of the Islamic world gathered in Samarkand, making it one of the most important intellectual hubs of the time. Timur valued the sciences, astronomy, and mathematics, encouraging the translation of Greek and Indian texts into Arabic and Persian. While his empire was built on the backs of conquests, his legacy as a statesman and patron of the arts gave birth to one of Central Asia’s most culturally significant dynasties: the Timurid dynasty. Even after his death in 1405, his descendants, including his grandson Ulugh Beg, continued to rule over Samarkand and its vast territories, creating a period of renaissance in the Islamic world. The Timurid dynasty is credited with fostering a unique blend of Persian, Turkic, and Mongol influences, which shaped the identity of modern Uzbekistan.

It’s A Mosaic World at Registan Square

Our first stop in Samarkand was the famous Registan Square that stands as a testament to the vision and opulence of Timur’s reign. The three madrasas—Ulugh Beg, Sher-Dor, and Tilya-Kori—feature intricate mosaic tilework, with deep blues, greens, and golds catching the light at every angle, be it in the day or during light show at night.

The Ulugh Beg Madrasa is the oldest of the three madrasas and was built in the 15th century by Ulugh Beg, the astronomer-king and grandson of Timur. More than just a place of Islamic learning, it was a hub for science, math, and astronomy—reflecting Ulugh Beg’s passion for knowledge. Its façade is decorated with complex geometric patterns and star motifs, hinting at the celestial interests of its founder. Standing before it, you can almost imagine scholars deep in study, tracing the stars from within its mosaic-covered walls.

Opposite Ulugh Beg’s madrasa is Sher-Dor which was built two centuries later by Yalangtoʻsh Bahodir. It mirrors the structure of its older neighbor but carries a bold and unique artistic twist—its name means “lion-bearing,” a reference to the striking tiger-lion figures chasing deer across the entrance arch. These animal designs were rare in Islamic art, making Sher-Dor both controversial and captivating. It symbolizes strength, ambition, and the attempt to revive the Timurid glory.

In between them stands Tilya-Kori, the golden centerpiece, built a decade after Sher-Dor by Yalangtoʻsh Bahodir. Part madrasa, part mosque, it’s named for its lavish interior—Tilya-Kori means “gilded” or “gold-covered.” Inside, the main prayer hall is breathtaking, with its gilded dome and shimmering walls. It served not only as a place of study but also as Samarkand’s central mosque at the time, uniting knowledge and worship under one dazzling roof.

While walking through Registan Square in the day was mesmerizing, it was equally lovely at sunset and after, when the crowds thinned and we could sit on the stairs right outside the complex. With a gentle breeze, moonlight, and a stunning view of the monuments lit up in different colours, the ambiance was very different from what we experienced in the day, but just as magical.

Life Beyond Death

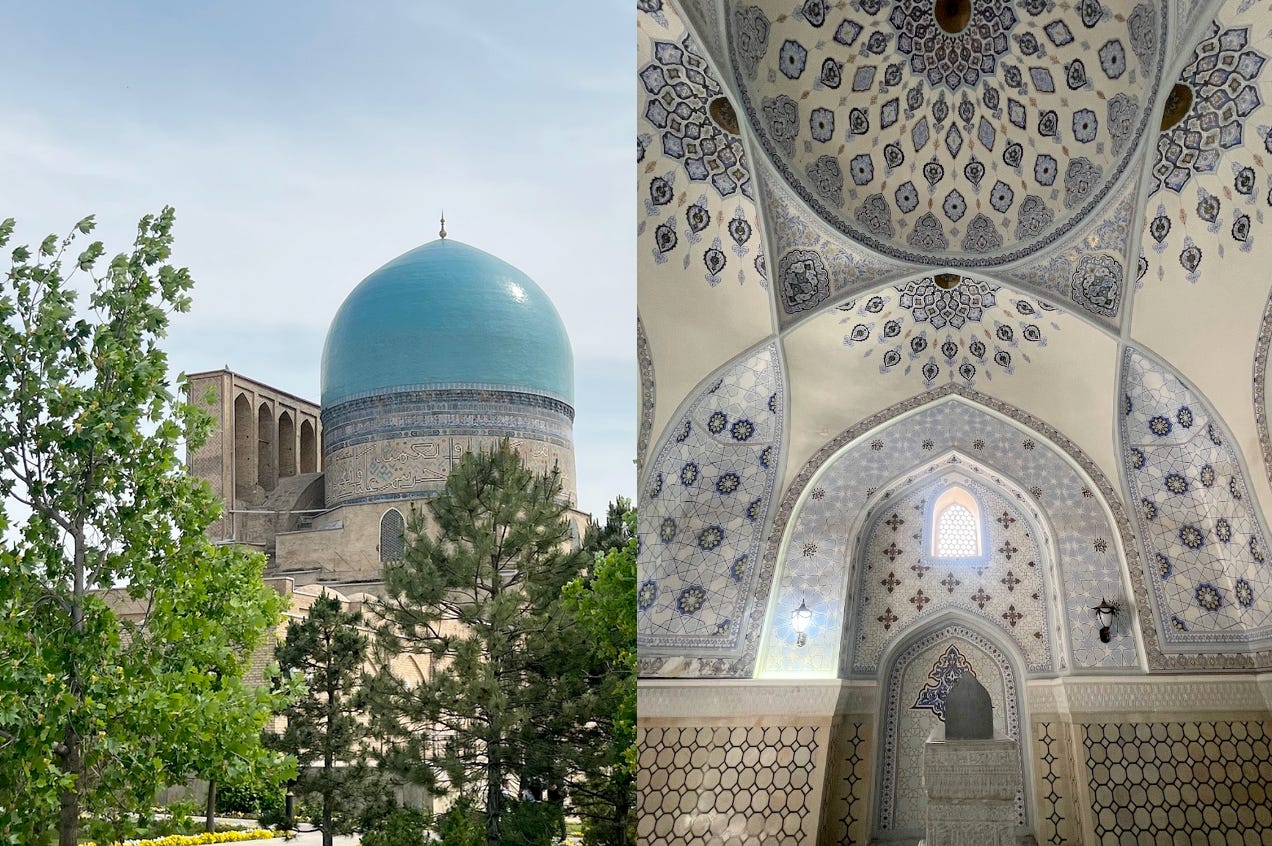

The Bibi-Khanym Mosque is considered to be a masterpiece of the Timurid Renaissance. Built in the 15th century, it was one of the largest and most magnificent mosques in the Islamic world.

Gur-e-Amir, the final resting place of Timur, is also located in Samarkand. Modest from the outside compared to his grand ambitions, the mausoleum surprises with its richly ornamented interior: a chamber bathed in deep blues, gold leaf, and solemn silence. Beneath its ribbed dome lies Timur’s simple jade tombstone, surrounded by his descendants, including the scholar-king Ulugh Beg.

One of the places I enjoyed the most was the Shah-i-Zinda—a narrow, tiled necropolis that felt like a portal through time. It’s believed to be the burial place of Qusam ibn Abbas, a cousin of the Prophet Muhammad and teacher of Timur. As you walk up the stone steps and into the corridor of turquoise domes and intricate mosaics, each mausoleum, built over centuries by Timurid royalty and nobility, tells a story in tile and stone.

Science at the Centre of Empire

The Ulugh Beg Observatory sits on a hill surrounded by trees and is a powerful reminder that science once stood at the center of empire. Built in the 15th century by Ulugh Beg—astronomer, mathematician, and ruler—it housed one of the most advanced instruments of its time: a massive sextant carved into the earth. Standing at the site, it's humbling to imagine scholars charting the stars centuries ago, even before the telescope was invented.

Ulugh Beg was a rare ruler who placed knowledge above warfare. As the grandson of Timur, he inherited not just an empire but a deep curiosity for the stars. As the governor of Samarkand, he turned the city into a center of science, culture, and learning. Despite living in an era of empire-building and political intrigue, Ulugh Beg is remembered not for conquests, but for charting the heavens and inspiring generations of scientists across the Islamic world and beyond. He also became unpopular with sufis and dervishes because of his views.

“Religions of the world dissipate like fog, kingdoms vanish, but it’s the work of scientists that remain for eternity.” - Ulugh Beg

A Glimpse of the Sogdians at Afrasiyab

The Afrasiyab Settlement is the ancient heart of Samarkand, dating back over 2,000 years. It was the original site of the city and the grand fortification in which the Sogdians stayed when they ruled Transoxiana, before being destroyed by the Mongols in the 13th century. Today, the Afrasiyab Museum offers a glimpse into a pre-Timurid Samarkand filled with Sogdian art, fragments of palace walls, and vivid murals that tell stories of daily life, wedding processions, and spiritual beliefs.

A Day Trip to Shahrisabz

Our trip would have been incomplete without a day trip to Shahrisabz, the birthplace of Timur, who was born to a noble family of the Turkic-Mongol Barlas tribe in then Transoxiana. Though not a direct descendant of Genghis Khan, he rose to power through a mix of military skill, political strategy, and sheer ambition. By his thirties, he had consolidated control over much of Central Asia, positioning himself as both a restorer of Mongol glory and the founder of a new empire centered in Samarkand.

Driving through the rolling countryside, we arrived at a place that, though quieter than Samarkand, held its own kind of grandeur. The towering ruins of the Ak Saray Palace—once Timur’s ambitious summer residence—gave us a sense of his vast vision, even in their weathered state. Nearby, we visited Jahangir’s tomb, built for Timur’s eldest son, whose early death reportedly broke the conqueror’s heart. The final stop was the Kok Gumbaz Mosque, with its striking blue dome and serene courtyard—a peaceful contrast to the scale of Timur’s monuments.

As we concluded the second leg of our trip, Rameen shared that the Mongols, led by Ghenghis Khan, had wiped out the city of Samarkand, and everything that stands today belongs to the post-Genghis era. Most of the monuments were in ruins until the Soviets restored them.

While it’s difficult to summarize the sequence of rulers and dynasties in a short travel blog, my key takeaway from Rameen’s history lectures was that most of the conflicts were between the settlers and the nomads. The nomads invaded the settlers and when they won, became the new settlers, who were eventually overthrown by a new set of nomads. This cycle repeated throughout history and shaped not just Samarkand, but much of Central Asia. Samarkand is, thus, not just a stop on the Silk Road—it’s a testament to survival and transformation.

Stay tuned for part III of this series.

Excellent. And such amazing pictures. Ulugh Begg is such a fascinating character.

The pictures are stunning! Every post you publish bumps Uzbekistan a few places up on my places-to-visit list.